Pico Iyer's uplifting new book, "Aflame"

Michael Shapiro in conversation with the renowned author on Thursday, Jan. 30

Did you know the word “silent” is an anagram for “listen”? I’ve been considering that while reading Pico Iyer’s transcendent new book, Aflame: Learning from Silence.

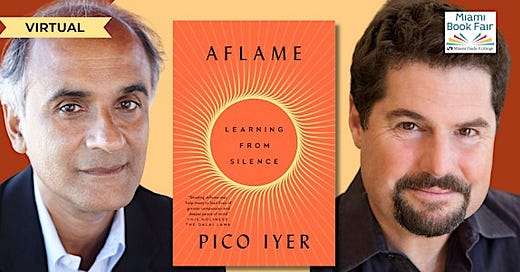

I have the good fortune and honor to interview Iyer for the Miami-based bookstore, Books & Books, on Zoom on Thursday, Jan. 30 at 7pm Eastern time, 4pm PT. Please join us via this link. More about Iyer and the new book below.

Speaking of listening (now that’s an unusual phrase!), I’ll be leading a two-part class called The Art of the Interview this Saturday Jan. 25 and Saturday Feb. 8 at Book Passage in Corte Madera, both from 10:30am to 12:30pm Pacific time.

I’ll be sharing strategies about conducting interviews for newspapers and magazines, (print and online) as well as for person-on-the-street interviews such as those found in Humans of New York. I’ll also suggest questions to ask during family history conversations, when interviewing parents or grandparents or others about their lives.

The class is both on Zoom and in-person at Book Passage bookstore in Corte Madera, Calif. Cost is $150 and there’s a 10% discount for those who have attended the Book Passage travel writers conference. To get the discount, go to this signup page and enter the code: shapiro10.

Pico Iyer’s Aflame

I just read Aflame, which came out last week. It’s a slim volume, 220 spacious pages, with a word count I’d typically cover in a night or two. But this is a book I wanted to savor.

Iyer writes of his more than 100 visits to a Benedictine hermitage on the precipitous Big Sur coast, the stillness and clarity he finds there, and the lifelong commitment and devotion of the monks who work long and hard days to provide peace and tranquility for visitors.

Iyer had thousands of pages of notes and could have written a hefty tome, but in Aflame every sentence is distilled to its essence.

As the title suggests, fire is a resonant theme. Iyer writes of losing his family home and the notes for his next three books decades ago in a cataclysmic fire in the Santa Barbara hills.

Fire looms like a specter over his beloved hermitage which faces the prospect every summer and autumn of infernal obliteration. The monks risk their lives to follow their heart.

Then there’s the symbolic flame of heightened consciousness that Iyer finds in solitude and contemplation, in nature and community, at the hermitage. An only child, Iyer finds his brothers at the hermitage.

When writing about exaltation and epiphanies, it can be easy to slip into cliches and self-absorbtion, but in Iyer’s deft hands, his prose is polished into gems.

“In my life below” the lofty hermitage, Iyer writes, “I'm so determined to make the most of every moment; here, simply watching a box of light above the bed, I'm ready at last to let every moment make the most of me.”

A fork in life’s road

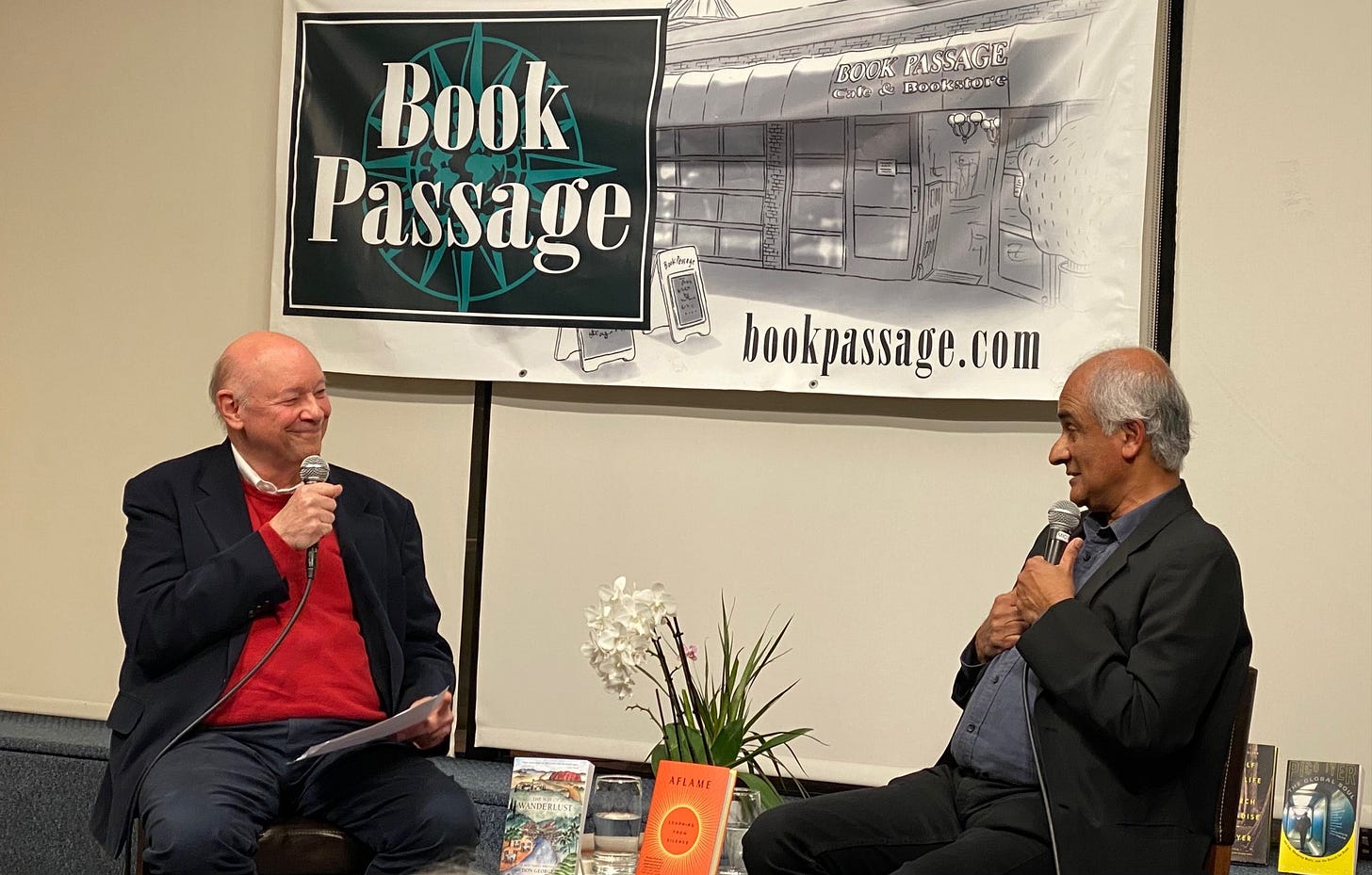

During the book launch last Wednesday at Book Passage, more than 200 people crowded into the store’s event space to hear Iyer in conversation with travel writer and editor Don George.

At the monastery, “I’m out of my head and come back to my senses,” Iyer said. “We have to awaken from the illusion of separateness.”

After the Santa Barbara fire that took his home more than 30 years ago, a friend suggested that Iyer retreat to the hermitage. There Iyer saw a fork in his life’s road with “success in one direction and joy in the other.”

Naturally, the exuberant author chose joy, but by most meaningful measures, he’s also found success: He lives with the love of his life in Japan, and his luminous books are treasured by readers, including the Dalai Lama.

Iyer also brings joy to his friends and admirers. His kindness is legendary: Legions of people count him as a dear friend, even if most of their communication with him is virtual.

Hope in the face of uncertainty

In this winter of unseasonable fires ravaging swaths of California and political tremors that can unmoor even the most grounded of us, Iyer’s book is a balm. It’s the work of a lifetime, a book that could only be written by an author who has practiced what Buddhists call right livelihood.

After beginning his career at Time magazine, Iyer published his first book, Video Night in Kathmandu in the late 1980s and became widely known as one of the world’s leading travel writers. At the hermitage, a woman seems surprised he’s there because “you’ve always seemed so happy with your life in the world.”

“The travel is interesting,” Iyer responds. “It keeps me in touch with the lives of others. The relief comes in getting to be one self.”

For a moment I wondered if “one self” was a typo, as it’s typically written “oneself.” Then I understood: At the hermitage, with its stunning vistas and crystalline silence, Iyer is able to integrate the many aspects of his identity and be “one self.”

While his travels have provided him with countless sights, Iyer discovers it’s quiet contemplation that offers a path to insight.

At the book launch last week, Iyer said he asks himself: “What can I bring to the ICU?” In other words, during life’s most wrenching moments, what do we have to offer?

Can we be of service, can our presence be healing and supportive and comforting? In the end, that’s worth more than a big bank account.

Aflame sparks so many thoughts. Last week in the midst of their conversation, Don George said, “I have five questions!” Without missing a beat, Iyer shot back, “And I have eleven answers!”

The salve of silence

There’s a poignant scene in Aflame in which Iyer visits his longtime friend, musician and poet Leonard Cohen, and after conversing they simply sit together in silence.

Iyer thinks this may be Cohen’s way of suggesting it’s time for Iyer to go, but when he moves to leave Cohen implores him to stay.

In the U.S. and much of the world, we’re going through a time of abrasive polarity. Any comment can be divisive. One remedy for this, Iyer suggests, is silence.

When we sit quietly with someone, we can often share more than when we speak. If we start talking, Iyer says, we can be at odds within seconds, but “silence can unite us.”

Hear, hear!